In a Death Penalty Case, Texas battles Mexico, Washington (and the World)

In a Death Penalty Case, Texas battles Mexico, Washington (and the World)By David Paulin

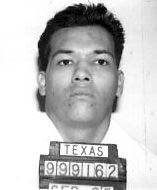

Humberto Leal Garcia Jr., a 38-year-old Mexican national, is scheduled to die by lethal injection on Thursday, July 7, in the Texas death chamber. He was convicted for the 1994 rape and murder of 16-year-old Adria Sauceda in San Antonio, Texas -- a crime that was particularly sordid as far as rapes and murders go.

Leal, however, isn't your typical death row inmate found guilty of an unspeakable crime. He has friends and supporters, mostly liberals: anti-death penalty advocates, law professors, and myriad others with various agendas. All have an international outlook -- and misplaced confidence in the efficacy of international law. One of them is President Obama.

Leal is now the object of a tug-of-war: Gov. Rick Perry and his Republican administration are on one side -- and on the other are Mexico's government, President Obama, and the International Court of Justice in The Hague. With the clock ticking down on Leal's life, this is a standoff between what liberals might call the forces of enlightenment (Obama and friends) and a gang of right-wing Christian zealots in Texas led by Gov. Perry.

At issue are lofty legal technicalities concerning international law: specifically, whether Texas violated the 1963 Vienna Convention in respect to Leal and is ignoring an edict from the International Court of Justice in The Hague on how it ought to be treating Mexicans accused of serious crimes in the state. Last Friday, lawyers for the Obama administration went to the U.S. Supreme Court seeking a stay of execution for Leal. Gov. Perry is determined not to grant it.

The case revolves around an alleged slip-up made by law-enforcement authorities in San Antonio. After arresting Leal, they failed to tell him that as a Mexican national, he had a right to contact Mexico's consular officials. Supposedly, Leal would have exercised that right -- and then Mexico's government would have provided him the best defense Mexico could buy.

Predictably, the mainstream media has given lots of sympathetic coverage to Leal in a case pitting Texas against Washington, Mexico -- and the world. As The New York Times recently put it: Leal "was denied his rights under the Vienna Convention to consult Mexican consular officials" (emphasis added). In fact, Leal wasn't denied anything. He simply wasn't told what his rights were under an obscure provision of the Vienna Convention concerning consular relations; it was often overlooked at the time by local police departments. The convention is signed by some 183 nations, including Mexico and the United States.

Why wouldn't Leal think to ask about seeing a consular official -- something most Americans would do if arrested in Mexico or other foreign country? Perhaps it was because Leal had been in the U.S. since he was 2 years old and regarded himself as an American. Or perhaps like many poor and uneducated Mexicans, Leal would be shocked to know that Mexico's government -- in spite of its notoriously corrupt and inefficient criminal justice system -- would be eager to provide him with top-notch defense lawyers.

Or perhaps San Antonio's police were caught in a Catch-22 situation. In many parts of Texas, police are forbidden to ask criminal suspects about their immigration status -- doing so is regarded as racist "profiling." Accordingly, police couldn't very well ask Leal if he was a Mexican and perhaps in the country illegally. Mexico's government has protested loudly against such outrages.

Of course, Mexico's sudden interest in citizens like Leal smacks of political grandstanding, motivated by the feeling that Texas and other parts of America have essentially become appendages of Mexico.

The lawyer whom Mexico has provided to defend Leal is Sandra L. Babcock, a law professor at Northwestern University. She seems to think that in another trial, she could raise enough doubts about her client's guilt that a jury would give him a life sentence. Among other things, she claims a Catholic priest raped Leal when he was a boy. But given the weight of evidence against Leal, it's inconceivable he'd be found innocent in another trial.

In coming to Leal's defense, the Obama administration claims that if the U.S. fails to do right by Leal, Americans abroad could be denied access to consular access when accused of crimes. Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli, Jr. wrote in a friend-of-the-court brief that executing Leal "would place the United States in irreparable breach of its international-law obligation to afford [Leal] review and reconsideration of his claim that his conviction and sentence were prejudiced by Texas authorities' failure to provide consular notification and assistance under the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations."

In another effort to save Leal, the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, has asked Gov. Perry to commute his death sentence to life in prison.

In Mexico, ordinary citizens can expect little from their country's criminal justice system; it's not a place where they can count on receiving justice. So it is surprising that Mexicans on death row in the U.S. can expect so much from their government. Americans, moreover, have always fared badly when caught in Mexico's criminal justice system; it's one of the risks of going to Mexico, and international law does not seem to offer additional guarantees of safety to visitors going there. Yet in this case and others, Mexico presents itself as a paragon of virtue, committed to the lofty ideals of international law that Texas and other U.S. states are ignoring.

In 2004, Mexico sent its top legal talent to the International Court of Justice in The Hague -- and complained about 51 of its citizens being on death rows in various U.S. states; none, they complained, had been advised that their government was prepared to offer them top lawyers for their defense.

That Hague court ruled that the U.S. was indeed bound by the treaty -- prompting President George W. Bush to ask the states to apply it and review cases involving Mexican citizens awaiting death sentences. However, Gov. Perry was unimpressed. He refused to grant a stay-of-execution for Jose Medellin, 33, an illegal immigrant from Mexico found guilty in the 1993 rape-strangulation of two teenage Houston girls, Jennifer Ertman and Elizabeth Peña. Instead, Medellin was executed, despite having never been informed that Mexico was ready to provide him with a great lawyer.

Jennifer's father, Randy Ertman, was outraged that international law was evoked in behalf of his daughter's killer. "It's just a last-ditch effort to keep the scumbag breathing," he said. "I don't care, I really don't care what anyone thinks about this except Texas. I love Texas. Texas is in my blood."

Gov. Perry was on firm legal ground in not ordering a stay-of-execution for Medellin to allow his case to be reviewed another time. The U.S. Supreme Court later ruled Congress needed to ratify the treaty, as the Senate had done, for it to become binding on U.S. states.

Earlier this year, the Council of Europe, the continent's highest human rights body, called for U.S. legislation to shore up the Vienna treaty -- thus making it binding on U.S. states. Of course, passing such legislation could become a political liability for lawmakers who care about what their constituents think about them -- rather than what a human-rights court in Europe thinks about them.

Ultimately, the Obama administration hopes Congress will ratify the Vienna treaty in the coming months -- and that granting Leal a stay-of-execution will buy him time. This could save him from the death chamber and possibly get him a new trial -- or commutation of his sentence to life.

Meanwhile, Senator Patrick Leahy, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, recently introduced legislation to help Leal and other foreign nationals who are facing death sentences -- but who were "denied" consular assistance. The bill would provide for an automatic federal review of their cases and, most importantly, require a stay of execution if necessary. Mexico must be a big fan of the Democratic senator from Vermont.

Leal's crime, of course, has been long forgotten amid the high-minded debate about his rights under the Vienna treaty. Sauceda, his victim, had been at a party the night she died, and alcohol and drugs were being passed around. She got drunk. Eventually, she ended up being gang-raped as young men took turns over her.

Leal, claiming to party-goers that he was Sauceda's friend, offered to give her a ride home. Later, Sauceda was found nude and bloodied in a field -- her head bashed in and bite marks over her body. To rape her, Leal used a stick about 15 inches long. He left it inside her when he'd finished. The stick, according to medical evidence, was used while she was alive -- and hence the rape charge.

Leal has had myriad legal motions and appeals filed in his behalf. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit stated that Leal was "overwhelmingly" guilty. Bite marks, DNA evidence, confessions Leal made to various people -- all helped to convict him. Ultimately, the court determined that whatever mistakes Leal's lawyers made, if any, were insignificant -- and that he got a fair trial. A new one would produce the same outcome.

How does the family of Adria Sauceda feel about how the case against Leal has evolved -- going from a heartbreaking rape and murder case to one in which Leal has become something of an international celebrity, a victim himself? Nobody in the mainstream media has ever thought to talk to them until the San Antonio Express-News ran a long front-page story last Sunday.

The family declined to talk about the controversy over Leal, but instead talked only about Adria. "It's like it was yesterday," said Rene Sauceda, her father. "The pain, it's like it just happened." What might the judges in The Hague think about that?

All in all, the case of Humberto Leal Jr. vs. Texas must be a fun subject for Professor Babcock to pontificate upon in the faculty lounge at Northwestern University.

Originally published at The American Thinker

1 comment:

You have observed very interesting details,Great posting..!

Post a Comment